Understanding Present Value Relations in Finance

- Ömer Aras

- Oct 12, 2024

- 3 min read

Updated: Nov 9, 2025

In finance, an asset is a sequence of cashflows. This statement seems a bit abstract, yet—it is a precise way to describe how value is created and measured. When we assess the worth of any asset, what we are really doing is estimating the future money it will generate, and determining what that stream of money is worth today.

An Example: Boeing’s Regional Jet Project

To illustrate this, consider a real business decision.

Boeing is evaluating whether to develop a new regional jet. The project is expected to take three years of development and cost roughly $850 million. After that, Boeing anticipates it can sell 30 planes per year, each priced at $41 million, with production costs of $33 million per unit. That leaves an annual profit of $8 million per plane, or $240 million in annual net cashflows.

This project, like any other, can be viewed as an asset. But its value does not lie in the aircraft design, the factory, or the materials. It lies in the future cash it is expected to produce, starting in year four and continuing each year thereafter. These future profits represent a sequence of cashflows, and to understand whether the project is worth pursuing, Boeing must calculate what that sequence is worth today.

Why the Timing of Cashflows Matters

A central insight in finance is that a dollar received in the future is worth less than a dollar received today. This is true for three reasons:

1. Opportunity cost – Money today can be invested elsewhere.

2. Risk – Future cashflows are uncertain.

3. Time preference – Most people prefer to receive money sooner rather than later.

As a result, we cannot simply add future profits to determine value. We must discount them to reflect their value today.

Time as a Currency: The Need for Conversion

To understand discounting, imagine that cashflows in different years are like different currencies. You would not combine euros and dollars without first converting them. Similarly, cashflows from different years cannot be combined without adjusting for time.

In finance, we do this using discount factors, which are essentially exchange rates across time. These are determined by the market, based on the return investors could expect elsewhere. This return is called the opportunity cost of capital, and it is denoted by r.

The value today of one dollar received in the future is given by:

So, if Boeing expects $240 million per year starting in year 4, each of those annual cashflows must be discounted back to the present using this formula.

The Present Value Formula

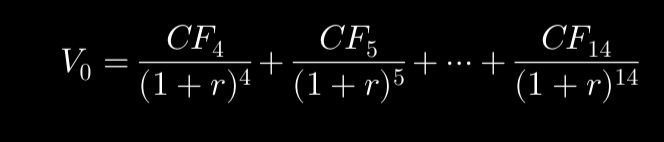

To calculate the total value of Boeing’s jet project today, we sum the present values of all future expected cashflows. If cashflows are expected from year 4 to, say, year 14, the formula becomes:

Here, each CFt is $240 million. The discount rate r is chosen based on Boeing’s cost of capital and the risk profile of the project.

Finally, we subtract the initial development cost of $850 million. If the resulting Net Present Value (NPV) is positive, Boeing should proceed. If it is negative, the project should be rejected.

A Real Number Example

Let’s assume Boeing uses a discount rate of 10% (i.e. r = 0.10) to reflect its cost of capital and risk level.

Boeing expects $240 million in annual profits from year 4 to year 10 (a 7-year stream). Here’s how to calculate the present value of just the year 4 cashflow:

This means that $240 million received in year 4 is worth about $163.89 million today.

You would repeat this for each year’s cashflow (from year 4 to year 10), discounting each one back to today. The total present value of all future profits might come out to, say, $1.3 billion(just as a hypothetical sum).

Then subtract the $850 million upfront cost to get the Net Present Value (NPV):

Since the NPV is positive, Boeing should accept the project.

How Is Value Determined?

The value of this project—and of any asset—depends on both objective and subjective factors.

Objective factors include:

• The size and timing of expected cashflows

• The discount rate, based on market conditions

• The number of years the cashflows will continue

Subjective factors include:

• Boeing’s expectations about future aircraft demand

• Their confidence in keeping production costs at $33 million

• Macroeconomic conditions and technological risks

So, even though the present value formula is mathematical, the inputs are based on judgment.

This is known as the Net Present Value (NPV) rule, and it lies at the heart of corporate finance. Although NPV is a subjective and simplistic measure, its fundamental logic underpins all complex financial models and remains applicable even in the most convoluted situations.

This blog entry was inspired by the MIT OpenCourseWare content on Finance

Comments