Thames Water: Drowning in Debt, Soaking the Public

- Ömer Aras

- Aug 2, 2024

- 4 min read

The economic terminology used throughout this text is provided and explained in the definition list at the end.

Thames Water is a private utility company based in the United Kingdom that provides water supply and wastewater treatment services. It serves around 15 million customers across London and the Thames Valley, making it the largest water and wastewater services provider in the country. The company is responsible for managing water reservoirs, treatment plants, and an extensive network of pipes and sewers. In addition to supplying clean drinking water, Thames Water handles the collection and treatment of sewage, ensuring public sanitation and environmental protection. Its operations cover both domestic and commercial customers, and it plays a vital role in maintaining essential infrastructure across the region.

This commentary analyzes the financial and operational challenges faced by Thames Water through the theoretical lens of natural monopoly. Given the high fixed costs and infrastructure needs in the water industry, it is more cost-efficient for one firm to serve the entire market rather than multiple competitors. Thames Water perfectly illustrates this natural monopoly structure.

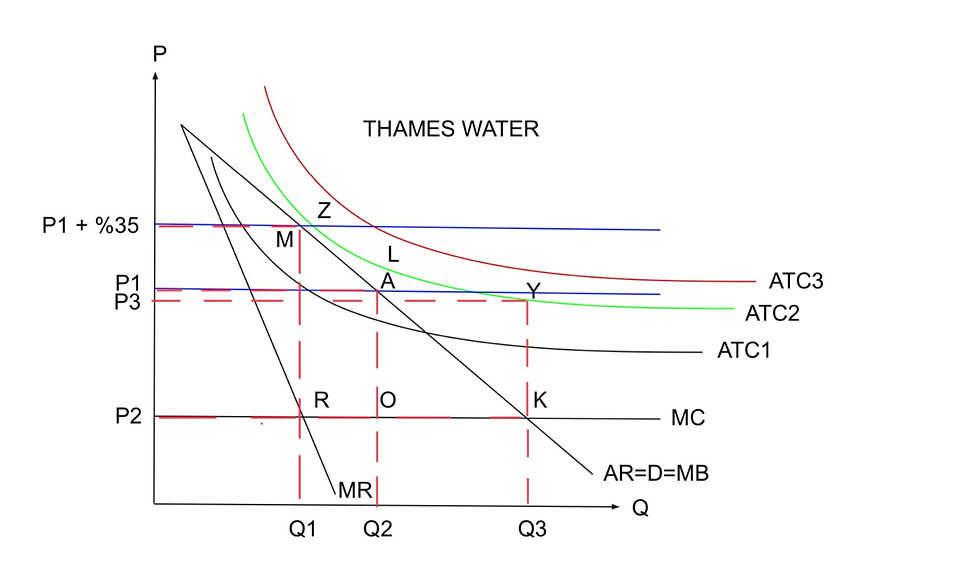

Despite its 100% market share, Thames Water is burdened by a debt of £19 billion. This unusual loss making situation can be explained in two ways by the diagram above. Either Thames Water is operating beyond point K due to regulatory oversight by Ofwat, the industry regulator. Or it is X-inefficient. The latter seems more probable because there is a absence of competition. The lack of competitors doesn’t put Thames Water to operate efficiently. This means Thames Water is not producing on the lowest possible ATC curve (ATC1). Instead, it operates on a higher average total cost curve (ATC2), which remains above the demand curve, resulting in losses at any output level.

In the last few months Thames requested a 35% price increase (from P1 to P1 + 35%). This suggests that by raising prices, Thames Water can minimize losses. If Thames Water were minimizing losses, it would operate at point M on the diagram, but this is not the case. Instead, it is constrained to operate at point A due to Ofwat’s price controls.

Consumers will face higher prices for a service that they already overpay for and that is underprovided relative to the allocatively efficient point (point M vs K). This indicates allocative inefficiency, shown as the area AOK on the diagram. A further price increase would worsen deadweight loss (area MRK). Thames Water also operates productively inefficiently (point L), failing to fully exploit economies of scale. Price increases would exacerbate productive inefficiencies (point Z), resulting in more wasteful resource use. Moreover, increasing prices redistributes income regressively from consumers to shareholders, disproportionately harming lower-income groups who spend a larger proportion of their income on water bills.

Financial difficulties have also contributed to underinvestment in infrastructure needed to prevent sewage overflows into rivers and seas, illustrating dynamic inefficiency. Lack of competitive pressure reduces Thames Water’s incentives to maintain and improve long-term service quality.

A retired Thames Water employee has suggested urgent government ownership to protect staff terms, conditions, and pensions. However, nationalization would place a burden on government budgets funded by taxpayers, especially if marginal cost pricing were introduced to eliminate allocative inefficiency (point K where MB=MC). At this point, Thames Water would incur losses (represented by the area P3P2KY), requiring subsidies. Public ownership may also reduce profit incentives, increasing inefficiencies (ATC2 shifting to ATC3), reducing innovation, and prioritizing social goals such as job preservation over operational efficiency.

Thames Water has also recently secured a £1.5 billion loan. If these funds are used to pay dividends or debts without operational improvements (these are things Thames has been actively engaging in), inefficiencies will persist. The judge even noted that he “might have been tempted to refuse to sanction the plan” because £800 million would be spent on interest costs and advisers. This suggests Thames Water plans to continue operating inefficiently. If creditors must absorb losses, it signals deep structural problems that risk further burdens on consumers.

In my opinion, Thames Water should be temporarily nationalized so the government can intervene directly to prioritize service quality and long-term investments rather than short-term debt repayments. Once stabilized and inefficiencies addressed, the company could be re-privatized with stricter regulations requiring reinvestment, limiting excessive dividends, and enforcing stronger penalties. Temporary nationalization could therefore reduce inefficiencies while preserving private sector incentives in the long run. While public ownership can also be inefficient due to weaker profit incentives and potential bureaucratic mismanagement, Thames Water is already in a deeply problematic state. In this context, temporary nationalization represents the best of a set of imperfect options.

DEFINITION LIST:

· Marginal Cost (MC): The additional cost incurred from producing one more unit of a good or service

· Fixed Cost: Costs that do not vary with the level of output, such as rent, salaries, or infrastructure expenses.

· Allocative Efficiency: A state of resource allocation where the value consumers place on a good (reflected by price) equals the cost of resources used to produce it (MC = MB)(MC=D), maximizing societal welfare.

· Dynamic Efficiency: Efficiency over time, achieved when firms invest in innovation and improvements to reduce costs and enhance product quality in the long run (shift of long run average total cost curve down)

· X-Inefficiency: When a firm produces output at higher costs than necessary due to a lack of competitive pressure, leading to waste of resources. (Operating above the lowest possible average total cost curve)

· Productive Inefficiency: When a firm is not producing at the lowest possible cost, meaning it is not fully utilizing its resources or economies of scale. (Operating at the lowest point on the current average total cost curve)

· Economies of Scale: Cost advantages that a firm experiences as it increases output, leading to a decrease in average cost per unit due to factors like bulk purchasing or specialization (Shift of average total cost downwards).

· Deadweight Loss: The loss of economic efficiency that occurs when the equilibrium outcome is not achieved, typically due to market distortions such as taxes, subsidies, price controls, or monopolistic pricing. It represents the total surplus (consumer and producer surplus) that is lost because trades that would have benefited both buyers and sellers do not occur.

Comments