Power, Progress, and the Politics of AI: Rethinking Technological Advancement for Shared Prosperity

- Ömer Aras

- Aug 10, 2024

- 4 min read

Nobel Economics prize winner Daron Acemoglu’s work, Power and Progress doesn’t just analyze how artificial intelligence is transforming society but it questions things we don’t even think about. His thesis is urgent: technological advancement, when left to market forces alone, tends to deepen inequality, entrench political manipulation, and erode democratic accountability.

Acemoglu takes us on a historical journey to show that the story of automation is not new. In fact, back in the 1930s, John Maynard Keynes warned about “technological unemployment” a new disease that he believed would accompany economic growth. He envisioned a future in which machines would displace human labor on mass sclae. He was partially wrong and partially correct. In agriculture, for example, the mechanization of the U.S. economy did away with nearly half the workforce. However the unemployment due to technology was smaller than the jobs created through new tasks.

What made this transformation possible, Acemoglu argues, was not technology alone it was the political and institutional context. The U.S. after WWII was home to both strong labor market institutions and active democratic reform. Government funding supported long-term scientific research. The tax system didn’t reward automation at the expense of labor. Antitrust actions prevented monopolies from capturing the future. And crucially, democracy expanded from the direct election of senators to the gains of the civil rights movement. This environment allowed technology to complement human labor, not simply replace it. Concisely, labour market institutions coexisted alongside technological improvements. The period was so succesfull that the French called it “les trente glorieuses”, the thirty glorious years.

After the 1970s the case turned to the opposite direction, real wages for most workers have stagnated, even as productivity has continue to rise. Income gains have disproportionately gone to the top 10%. The reasons are structural: the real value of the minimum wage has dropped over 30% since 1968. Manufacturing jobs disappeared in the US, particularly due to the rise of China. Automation increasingly substituted for blue-collar work, while it complements white-collar labor. As a result, inequality grew. Not because technology is evil, but because its application is skewed.

AI, Acemoglu argues, may be the critical point. What started in the 1950s as an ambitious dream to replicate human thought has evolved into a industry dominated by a handful of powerful tech firms. AI no longer aims at mimicking intelligence but it optimizes prediction, extracts patterns, and reduces labor demand. However this case is not because of AI itself but because of the monopoly power, lack of government response and lack of democracy.

In the past, governments spent money on “blue-sky” research projects that didn’t have immediate profit but helped create entirely new industries and jobs. Now, that kind of support has dropped. At the same time, protections for workers have gotten weaker. Labor unions have less power, and many people don’t have job security. On top of this, the biggest companies today are the ones that focus on replacing workers with machines. These companies now lead the economy and set the rules. Even the tax system encourages this: companies pay less tax when they buy machines, but labor costs are taxed more. Democracy is also getting weaker. Politics in the U.S. has become more divided, the media listens less to different views, and money plays a bigger role in shaping political decisions. All of this gives more power to big companies and makes it easier for them to use AI in ways that don’t help most people

AI tools are increasingly used for political purposes. Social media algorithms now amplify division and spread personalized disinformation, weakening democratic debate. The Cambridge Analytica scandal showed how data and AI were used to manipulate voters during major elections. Even in democracies, AI has become a tool for surveillance. Edward Snowden’s revelations showed how governments can use it to monitor citizens, raising serious concerns about liberty and control.

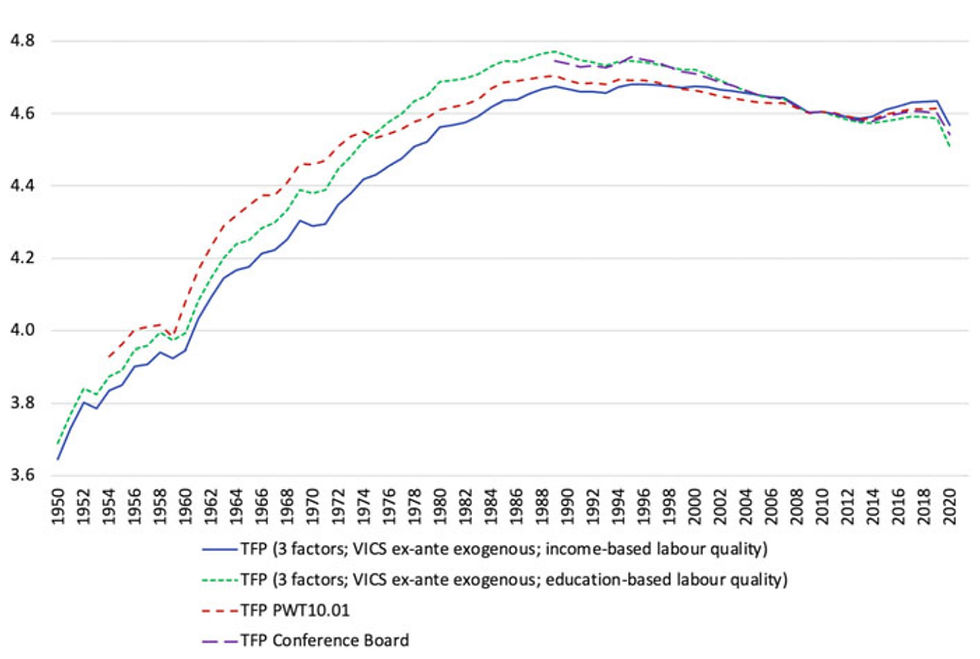

The market is not automatically choosing the best path for society. Therefore we should intervene. From 1930 to 1970, the U.S. saw strong growth in total factor productivity (how much aggregate income would change if the quantities of capital and labor stayed the same, but productivity (e.g. due to better technology) improved) at around 2% on average. Since 1990, that has dropped to 0.5%. Meanwhile, technologies like surveillance AI create negative externalities that the market doesn’t account for. Left alone, innovation doesn’t always serve the public good.

Redistrivutive measures are also insufficient. They are only useful as helping mechanisms. As Acemoğlu states, building shared prodperity predominantly based on redistribution is a fantasy.

Moreover much of the control over AI lies with private corporations. Government funding for basic research, the kind that once sparked breakthroughs, has declined. Therefore private institutions possess monopoly power over AI research. These firms also influence what gets taught at universities. As a result, students entering AI often focus on building tools that can be commercialized, not those that solve public needs.

To fix this, we need to change course. First, remove government policies that favor automation. For example, in the U.S., software is taxed at just 5%, while labor is taxed at 25%. This encourages companies to replace people with machines. Second, we need better ways to measure technology’s impact not just how many jobs it replaces, but how many new ones it creates. Finally, we must demand more democratic oversight. When decisions are made without public input or transparency, it’s easy for harmful effects to keep happening.

Comments